On February 28, 15 years ago, 100 photographers from 26 countries descended on Africa to document the continent for the book “A Day in the Life of Africa”.

Early morning training run along the edge of the Great Rift Valley

The complexity of the project was overwhelming. At least one photographer was assigned one of the 55 countries and everyone had to be in place for the day of the shoot.

The great French editorial director Eliane Laffont was asked to select the group to be invited with the brief “We want the very best photojournalists working in the world today.” With the caveat that they had to have had on the ground experience in Africa, project director David Cohen added “that this is no place for amateurs or first-timers.” The group included Ed Kashi, Yann Arthus-Bertrand, George Steinmetz, James Nachtwey, Sebastiao Salgado, Bruno Barbey, the Turnley twins and Susan Meiselas. An impressive line up.

My choice of assignment was Mauritania that at the time had the world’s largest refugee camp. I applied for my visa and waited, and waited.

To add to the complexity of the project, this was the first book to be shot entirely with digital cameras at a time when only a handful of us had ever used them. Olympus sponsored the project and issued every photographer with a state-of-the-art E20 DSLR that delivered a staggering 5-megapixel resolution! This plunge into the unknown necessitated a crash course immediately before the shoot and we all met in Paris a few days before flying off to Africa. It was likened to giving Roger Federer a new tennis racket minutes before the Wimbledon final. It was more like giving him a squash racket to play with. I still didn’t have my visa for Mauritania.

I was told by the Mauritanian Mission in the US that the visa would be easy to get in Paris but even a couple of days before we were due to leave for Africa it hadn’t come through. I had to make a last minute switch of countries and flew to Kenya with Magnum’s Chris Steele-Perkins hoping to get a visa for Kenya on arrival. My assignment was in Eldoret, a nondescript town close to the Ugandan border to cover the legendary Kenyan distance runner Kip Keino.

This wasn’t the Kenya of Masai tribesmen and exotic animals. Tourists rarely visit Eldoret that sits at 7,000 feet on the edge of the Rift Valley, a 5-hour drive Northwest of Nairobi. My driver warned me that we might have to take evasive action if the road was blocked. Hijacking was commonplace. Abandoned cars were often found without their occupants but I had no intention of going missing.

I was hosted by the Eldoret Club, a classic colonial expats club on the outskirts of town complete with a residual population of gin-soaked expats although the club was now for local professionals and efficiently run by Kenyans. I was told quite firmly by the staff that I should avoid going into town after dark. I didn’t argue.

Eldoret, Kenya

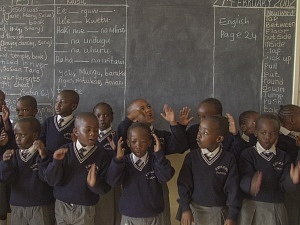

Kip Keino however was delightful. His parents died when he was a child, he was raised by an aunt and went on to become a 4-time Olympic medalist. He channeled his fame into philanthropic work and established both an orphanage and school. This was the focus of my coverage but I also included the training of long distance runners who still dominate the sport today.

Kip Keino school, Eldoret

The challenge with these short shoots is capturing something meaningful. I didn’t have much time for research; this was 15 years ago and Internet research was in its infancy.

I try to go into any assignment with an open mind and absorb as much as I can by intuition and osmosis. I ask a lot of questions, try to be a keen observer and melt into the situation. There used to be a time when 2 weeks was considered a short assignment. Today it can be 2 days assuming you can even get an assignment.

Pre-dawn exercises on the edge of the Great Rift Valley

I remember several years ago I was invited to photograph Bermuda for the Bermuda Tourist Board along with Bill Garrett, the former editor of National Geographic Magazine and he complained that he couldn’t expect to take photographs until he had spent a couple of weeks on location without picking up a camera. This is how it happened in the glory days of National Geographic. The world of magazines has changed and we have to adapt to a different approach. It’s far from ideal but unless you can self-finance the shoot we have to live with it.

I have always felt that the freshest impressions are during the first few days and this certainly worked for my Kenya assignment. I was given an opening spread in the book and also the opening photo essay. I was happy.